|

The First World War witnessed the consequences of

the new and potent means of warfare at sea – the submarine. The German

U-boat, as it was termed, became a grave and serious threat that

inflicted considerable losses on Allied shipping. This led to

significant changes in naval tactics and strenuous research efforts in

the development of hydrophones and increasing the capability of

underwater sound detection during and after the war.

The German U-boat threat returned with a vengeance

in the Second World War and became an intractable problem with the

grievous loss of life, materials and ships in the convoys. It was the

combination of two separate events that not only enabled the Allies to

eventually overcome and defeat the U-boats, but also contributed to the

development of recorded high fidelity sound and the commercial post war

success of the Decca Record Company.

The first occurred in May 1941, when Professor

Blackett, head of the Admiralty's Anti-Submarine Warfare Committee

presented a research proposal to develop an air-launched expendable

sonobuoy for use by Coastal Command to locate and destroy submarines.

He envisaged a small self-contained unit combining a hydrophone, radio

transmitter, battery pack and small parachute fitted into an expendable

buoy that would function for several hours before sinking. Blackett was

concerned about the limited availability of resources and suggested

that the Americans may be able to assist.1

The proposal was passed to Dr Pye at the Ministry

of Aircraft Production who recognised the potential and also agreed

with Blackett’s concern about the limitation on resources to undertake

the research, test and manufacture of the sonobuoy. He wrote to Dr

Darwin, Director of the Central Scientific Office in Washington DC, to

advise him of the idea and enquire if American help would be available.

It transpired that the Americans were already working on a similar

project with sonobuoys deployed from ships to act as ‘gatekeepers’ for

convoys.2

The

trials had limited success and the project was eventually stopped

because of other more pressing priorities. However, the airborne option

was taken up and the first successful test took place in March 1942.3

The operational sonobuoy was cylinder shaped,

approximately 3 feet in length and 5 inches in diameter. The top housed

the parachute and VHF radio transmitter, with the hydrophone deployed

from the bottom on a wire approximately 20 foot long. The casing was a

thick paper tube covered in resin. The transmitting range was

approximately 5 miles. Later models had metal casing, some with extra

battery packs, and were designed to be recoverable. The first sonobuoy

model, AN/CRT-1 and the accompanying radio receivers went into

full-scale production and entered active service in 1942/43.

This joint effort between Britain and the United

States provided a significant and effective step forward in

antisubmarine warfare. Sonobuoys were dropped, usually five at a time

with each tuned to a different radio frequency, in a pattern to enable

aircrews to listen and locate a submarine more accurately before

attacking.4

The Columbia University Division of War Research,

based at

the US Navy Underwater Sound Laboratory produced a series of training

gramophone records with various submarine sounds recorded from

sonobuoys. These sets became a part of Coastal Command’s training

syllabus. 5

The second event was the capture

of U-570, a type

VIIC submarine, on 27

August 1941, south of Iceland in the North Atlantic. While on her first

operational patrol a Coastal Command Hudson from 269 Squadron operating

from Kaldadarnes in Iceland surprised the U-Boat on the surface in bad

weather and dropped depth charges forcing the crew out onto the casing

to surrender.

|

The vessel sustained damage during her

capture and

was

towed to Iceland for repairs. She was subsequently sailed to

Barrow-in-Furness by a British crew with a naval escort. The Admiralty

took the golden opportunity to forensically examine the newly completed

vessel (April 1941) by testing and measuring every aspect of its

construction, equipment and performance.6

|

U570 in Barrow-in-Furness

Royal Navy official photographer -

photograph

FL 951 from the Imperial War Museum. |

After additional repairs she was renamed HMS Graph

and underwent further extensive analysis of her seagoing performance

and equipment. This included sound trials at sea and at the Admiralty

Research Laboratory's acoustic range in Loch Goil, a small sea loch on

the Cowal peninsula in Argyll and Bute, Scotland. During extensive

comparative tests, that included another submarine HMS Sturgeon, it was

discovered that the sound profile of the German vessel had a

distinctively higher frequency range.7

Although higher frequencies could be broadcast and

measured they could

not be reproduced. The bandwidth of sound on gramophone records was

typically 50-4000Hz, while the nominal range of human hearing is

20-20,000Hz. The means of reproduction was also rudimentary, hence

78rpm shellac records sound compressed, particularly the higher

frequencies.

One of the key difficulties was that cutting heads

tended to modulate at around 4000Hz which prevented a wider bandwidth

being transferred to disc.8 Arthur

Haddy, Decca’s chief recording

engineer, was based at the Company’s Broadhurst Gardens studios in West

Hampstead and had been working for sometime on the means of increasing

recorded bandwidth. Using the nearby laboratory of Haynes Radio,9

he had experimented with a moving-coil rather than moving-iron cutting

head and by 1939 had successfully increased the upper range to around

7500Hz.10

By 1939, the Decca Company had been established

for ten years and had just emerged from a difficult financial period

and was now on a firmer footing. The company was not on the initial

list of official government contractors but had come to the attention

of the Admiralty through their proposal for an accurate navigational

system, subsequently code-named QM and successfully deployed as part of

Operation Neptune on D-Day.11

Coastal Command needed recordings up to 12,000Hz

for training crews to accurately interpret and identify what they were

hearing from sonobuoy transmissions and crucially the difference

between British and German vessels. Their request presented Decca with

a significant challenge and as Haddy explained: "We went all out with

high fidelity in a way that would have taken years in peacetime." 12

Haddy was also aware that part of the issue was

‘friendly fire’. Coastal Command crews worked in challenging and noisy

conditions that presented significant difficulties in listening to

sounds transmitted from sonobuoys and accurately identifying the

source.

With a small team of assistants Haddy set about

tackling the challenge. He eventually developed a cutting head that

increased the frequency range, so enabling the full frequency range of

sound from German U-Boats to be recorded.13

At Loch Goil further tests and recordings took

place involving HMS Graph and HMS Satyr.14 Haddy

noted that:

"A German submarine sounded quite different from an English submarine.

There was no mistaking it once you knew what to listen for. But the

tell tale difference was a very high frequency sound. [..] We had to

build a disc cutter that would handle the full range of human hearing.

We built one that would go up to around 16kHz. Then we recorded the

propeller noise of a captured German sub. Also the noise of a British

sub. On headphones you could clearly hear the difference." 15

Records were subsequently produced and distributed

to Coastal Command for training purposes. The potential for recorded

music was soon realised and the new process was coined Full Frequency

Range Recording (ffrr). Francis Attwood, the Company's advertising

manager, came up with the idea of ffrr emerging from an ear – the birth

of the famous logo.16

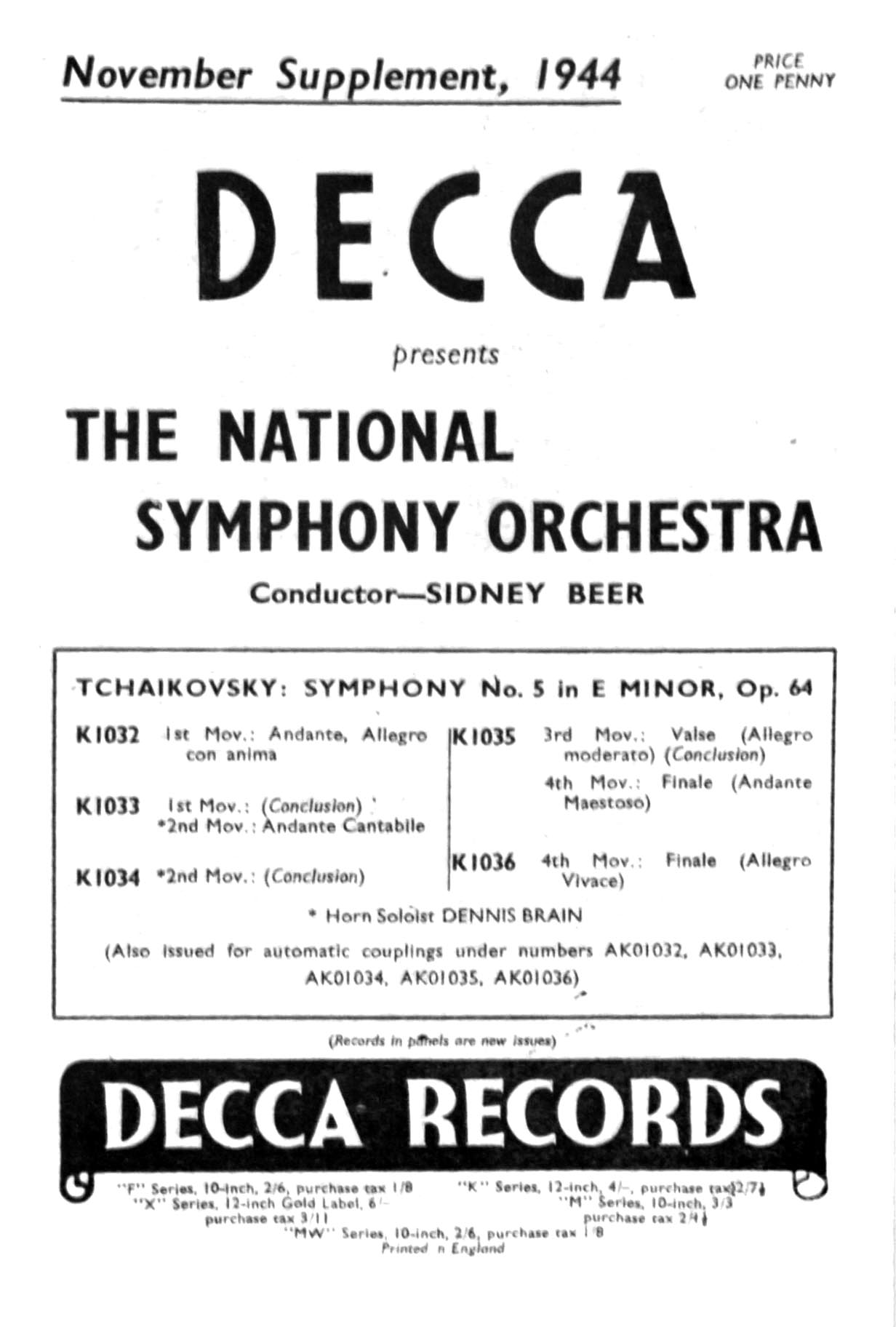

The first music recording using the new process

was

made at the Kingsway Hall in London during May 1944, heralding a new

era in recorded sound. Sidney Beer conducted the National Symphony

Orchestra in a performance of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No.5 in E minor,

Op.64.17

|

Haddy recalled that the first recording was

rejected and had to be re-recorded. The waxes were sent from the studio

to the pressing plant at New Malden on 6 June 1944.18

The recording was released in November 1944

without fanfare although the December 1944 edition of the Gramophone

carried a full page advert. In this edition the reviewer JPP noted that

it was 'technically, a very satisfactory recording’.19

The

official announcement for ffrr was not made until June 1945, by which

time the Company had released numerous records using the new process.

|

|

The records were soon followed in 1947 by the

Decola radiogram, designed by Harvey Schwarz, Decca’s chief radio

engineer, which would set a new standard in sound reproduction. It had

a lightweight pick-up and the first with an elliptical stylus.20

The post war success and reputation of the Decca

Company and ‘Decca Sound’ was entirely attributable to countermeasures

developed during the U-boat war.

|

HMS Graph (U570) provided a very significant

contribution to the anti-submarine war effort and after the various

trials and tests she was deployed on active service. However,

maintenance issues and a lack of spare parts led to her being

decommissioned and eventually earmarked for scrapping.

|

HMS Graph in the Clyde. IWM collection (A16040) |

In March 1944

whilst being towed from Chatham to the Clyde she foundered on rocks at

Coul Point on the west coast of Islay and was abandoned.

The sonobuoy proved to be an effective means of

countering and overcoming the U-boat threat and helped to decisively

shift the balance of power in the Allies’ favour. It was subsequently

developed into a more sophisticated and technically capable device and

an effective countermeasure in anti-submarine warfare, particularly

during the Cold War era.

By the end of the war the Admiralty had

established an extensive library of gramophone records with underwater

recordings of every conceivable mechanical and animal noise in varying

water temperatures and depth. It would seem that none of the records

produced during the war have survived, only tantalising references in

some of the surviving documentation. However, the Royal Navy Submarine

Museum at Gosport has a collection of post war gramophone records

covering many aspects of underwater sound.

The gramophone record provided the vital link

between technical innovation and a chance encounter at sea. War often

provides the catalyst and impetus for innovation and technological

development. This was certainly true in the case of the Decca Record

Company whose significant contribution in the development of recorded

sound was the legacy of a prevailing military imperative.

Dr Tony Wakeford

Chairman

Friends of The

National Archives, Kew, London

Notes

- The National Archives, AVIA 42/22, outline

proposal dated 18 May 1941. This was enclosed with Pye’s letter dated

24 May 1941.

- Roger A. Holler ‘The evolution of the sonobuoy

from World War II to the Cold War’, in U.S. Navy Journal of Underwater

Acoustics, January 2014, pp.322-346..

- The National Archives, AVIA 42/22, a contract

with the RCA Manufacturing Company, Camden, New Jersey, was

subsequently drawn up in October 1941.

- The National Archives, ADM 1/15194 and AIR

2/12711, the development of sonobuoys.

- The National Archives, AIR 15/584, the

gramophone record set identified as D 16 series.

- The National Archives, ADM 239/358, report on

U570 (HMS Graph).

- The National Archives, ADM 1/15192, a 54 day

programme of operational sea-going trials was undertaken beginning in

February 1942, including making sound recordings. A sound trials report

can be found in ADM 204/2215.

- British Library Sound Archive, C90/08/01.

Harvey Schwarz interviewed by Laurence Stapley, Oral History of

Recorded Sound Series, 1983. Schwarz was Decca’s chief radio engineer.

- British Library Sound Archive, C90/16/01,

Arthur Haddy interviewed by Laurence Stapley, Oral History of Recorded

Sound Series, 1983.

- British Library Sound Archive, C90/21/01,

Kenneth

Wilkinson interviewed by Laurence Stapley, Oral History of Recorded

Sound Series, 1983. Wilkinson was a recording engineer who worked with

Haddy.

- The National Archives, ADM 1/15152, Decca

Navigational Aid. Reports and Trials.

- Mike Ashman, 2015, 'When Hi-Fi Came of Age' in

Gramophone, March 2015, p.20.

- British Library Sound Archive, C1403/1, ibid.

Haddy noted that the incidence of 'friendly fire' on British submarines

was eliminated as a result.

- The National Archives, ADM 253/478, High

frequency sound output from submarines.

- Barry Fox, ‘Hi-fi and the Second World War’ in

New Scientist, 3 November 1983, p.356. Barry Fox interviewed Arthur

Haddy about his experiences and contribution to recording sound at high

quality.

- Edward Lewis, 1956, No C.I.C., p.84.

- Decca 12 inch 78s, K1032-6 and auto-coupled

version AK1032-6.

- British Library Sound Archive, C1403/1 [Decca Classcial, 1929-2009 by Philip

Stuart, published in 2011, states this recording was made on 8

June 1944 along with works by Grieg, Debussy and Delius. The second

movement had been recorded experimentally on 12 May 1944]

- Gramophone, December 1944, pp.i and 81-82

- British Library Sound Archive, C90/08/01, ibid.

Around 5000 were sold, retailing between £200 and £500, depending upon

the model. The full potential of ffrr would become fully apparent when

the first vinyl long-playing records were introduced in June 1950.

This is an edited version of the article that

appears in

Magna, the Friends’ magazine, and is reproduced with the kind

permission of the trustees.

ffrr at 75

On 8 June 1945 Decca released their full

frequency

range recordings to the record buying public. It was exactly a year

since Decca started recording in ffrr

and during that year they engaged Sidney Beer's National

Symphony Orchestra to make recordings in ffrr.

To mark the 75th anniversary of the advent of ffrr we are releasing four albums

by the National Symphony Orchestra during March and April.

Read

Brian Wilson's article.

|